The Blonde Interpreter – Part 4

I must say that the start of my career as a freelance interpreter is a bit of a blur. I know I emailed as many of the Institute of Translation and Interpreting’s corporate members as I could, having first checked on their websites whether they seemed to provide Japanese interpreting services, and whether they preferred to accept applications by email or via a web form. As the fact that these agencies were members of ITI suggests, they were mainly UK-based. It wasn’t till years later that I realised I should probably be reaching out to Japanese agencies as well, though somehow I did find one or two UK-based agencies specialising in Japanese.

My CV back then was sparse, as are those of most interpreters newly starting out, but I had a number of advantages. I had been to a good University and got a good grade, I had an MA in Interpreting and Translation, and I had some practical experience of interpreting in the form of Peace Boat. Part of me was hoping that my experience working at NEC, along with the very few opportunities it had afforded me to interpret for real-life corporate types, would convince agencies that I had some basic knowledge in the field of telecommunications (or PR, or corporate planning), that might make me a suitable candidate for interpreting jobs in those fields. I’m not sure how convincing I was in that respect, as I don’t recall getting many telecoms-related jobs, either then or later.

Another thing I had in my favour was the interpreting work I had already started doing on the side whilst working at NEC, including a number of jobs for the Japan Foundation in London. As with many of the jobs I ended up doing back then, I don’t really remember how I got them; they are best described as the result of being in the right place at the right time. In this case, I think it was a friend from my course at Bath who let me know that the Japan Foundation were looking for an interpreter for one of their events. The Senior Programme Officer was wary of me at first. I remember we met in a café near her office well in advance of the event, and that she came armed with pages of information on the topic at hand (which was, as I recall, sound art) to aid my preparation. Would all clients be this thoughtful and considerate, I wondered? Scheduling a briefing in advance (unpaid, I should add), gathering armfuls of material to help me prepare for what was, at the end of the day, a 90-minute artist talk… The answer, as it turns out, was “no”. That the briefing was a one off was in fact to be taken as a sign of trust. After my first assignment, I had passed the test, and I was left to my own devices when it came to preparation going forward. I was grateful at the time that she took a punt on me, and I am grateful that the Foundation has been a regular client ever since, as well as one of my most reliable recommenders.

Some agencies replied, most didn’t. The ones that did mostly offered translation work, and that was fine: I needed to make a living. Thinking about it now, the agencies I have stayed in touch with over the years are the ones I met in person. They tend to be small (although some have since been bought out by larger outfits), and value the personal touch. They may or may not specialise in Japanese, but they are the ones who send a personal email rather than a blanket anonymous “dear translator/linguist”. Some even pick up the phone to me. Nowadays I have to turn down more of their work than I accept, but I am always happy to recommend a trusted colleague. Needless to say, these are the kind of agencies where staff turnover is low; they clearly value their own staff as much as their linguists.

Likewise, the Japanese agencies I’ve worked with the most have been the ones I met at some kind of language fair early on in my career. I don’t remember what the events were, but I remember coming away with lots of leaflets from Japanese agencies, and contacting them religiously. More recently, on a trip to Japan, I made appointments to visit some of the larger and more well-known Japanese agencies. Apart from annual reminder emails to confirm my details and rates and re-sign their contracts, I rarely, if ever, hear from them.

I very quickly joined J-Net, the Japanese network of the UK’s Institute of Translation and Interpreting, and made use of the opportunities it afforded to network with other Japanese interpreters and translators. My sempais were generous with their advice, and I discovered that one of the best ways to find work was via the recommendations of respected colleagues. I have now just about come to terms with the fact that I am now more or a less a sempai myself – at least to some. It feels good to be able to take on that role – advising, encouraging, and demonstrating to newcomers to the field how many amazing opportunities this career can offer.

Wonderful though the course at Bath was, one thing it didn’t teach was pricing and negotiation. That’s not to say that we didn’t receive any guidance on the subject. Every so often when I have a clear-out of my office, I come across a set of hand-written lecture notes – effectively a list of rates that we might expect to be paid for different types of jobs, differentiating between direct and agency, UK client and Japanese client, simultaneous and consecutive, business and public service, and varying levels of experience. Initially, this was all I had to go on when it came to setting my rates. Not that there was always much setting involved. Often, I was told how much I would be paid, and I could take it or leave it. Plus ça change.

Certain interactions and snippets of advice stand out in my memory. The French-English AIIC member, a friend of a friend, who exclaimed how lucky I was to have such a rare language combination, and told me that if she were me she “wouldn’t get out of bed” for less than x-hundred pounds (significantly more than I was charging at the time.). One of my first proper simultaneous interpreting jobs (an NGO meeting) for which the agent apologised that they could only offer £350… which was more than I had ever charged and made me realise that maybe there was something to what I was being told.

I don’t recall making any specific mistakes as I tried to establish myself, though I have no doubt that I made many. Perhaps at the time I was too inexperienced to even realise when I was doing anything wrong. I didn’t know what I didn’t know. Every job was a learning experience, every interaction with an agency or client was an opportunity to practice, whether I got the job or not.

Little by little, my confidence grew. Clients became repeat clients and then regulars (whether that meant once a month or once a year). I got used to interpreting for artists and creative types and learnt to trust my instincts when it came to interpreting (in the non-linguistic sense) their unique ways of expressing themselves. I loved the feedback I got from audiences in public-facing events. On more than one occasion, after interpreting what was almost a stream of consciousness for an artist with a particularly complicated train of thought, I would be approached by a Japanese audience member who would tell me that they hadn’t understood what the speaker was saying until I translated it into English. This was invariably a huge relief, since I always half expected those audience members who spoke both languages (who sometimes made up as much as half the audience) to pick holes in my renditions.

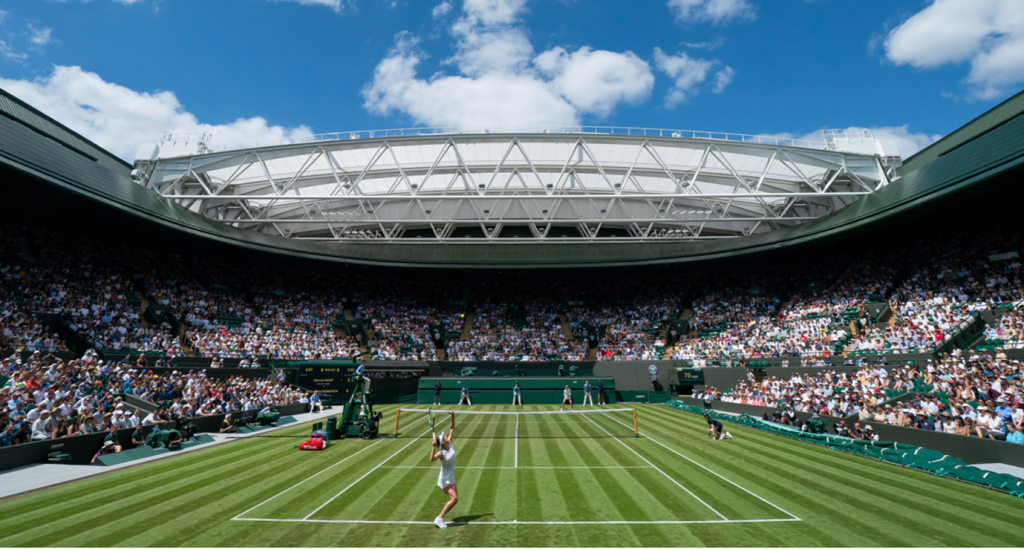

The very first job I did after leaving full-time employment was for NHK at Wimbledon. I knew nothing about tennis, and the pay was low (low enough that it was obvious even to me that I was probably making less than minimum wage) but it seemed like a great opportunity. This, I soon realised, was what freelancing was all about: the freedom to seize whatever opportunity came along and see where it might lead. Later, these opportunities would take me in front of the camera, but for now, I was firmly behind the scenes.

Working as part of a team supporting the NHK presenters and crew reminded me of the close-knit interpreting team on-board the Peace Boat. Between us we translated the daily tournament newsletters. We ran errands, collecting and translating press releases, saving spots for camera operators, and sitting in on player press conferences. Every day we would compile a list for the commentators of any celebrities and dignitaries due to be making an appearance that day, complete with short biographies and photographs. These lists were a vital tool for the commentators, whose commentary would accompany footage from the BBC, meaning that every so often, the camera would cut to the VIP box to show the famous faces of the day. Famous, that is, to a British audience (and sometimes not even that) – not so much to a Japanese one. It was up to the commentators to know who they were so that the Japanese audience didn’t feel quite so lost. This was perhaps the most nerve-racking element of the “interpreters’” job – standing behind the commentators in their box with the sole purpose of recognising these people when they appeared on screen and pointing to the right name in that morning’s VIP list, providing titbits of information that would allow the audience to recognise, say, the latest Doctor Who, or the Chair of the All England Club.

A couple of years later, the combination of sports and broadcasting brought another (this time slightly more lucrative) opportunity my way, in the form of a job at the 2012 London Olympics. It felt as though every freelancer in London who spoke English and Japanese was recruited by one Japanese broadcaster or another – in my case, TBS. The job went from the sublime to the ridiculous. I started out as personal interpreter for Masahiro Nakai, who was the main host of TBS’s Olympic programming. Then, once he had left, I was demoted to general dogsbody, tasked with buying sandwiches and photocopying! The experience was hectic, joyous, and truly once-in-a-lifetime. I had the honour of attending the opening ceremony, and – for a long time my biggest claim to fame – posing a single question to Usain Bolt for a Japanese interviewer who didn’t speak English.

Having majored in Japanese at University, and without any specialist knowledge per se under my belt, I never expected to specialise in anything in particular. Part of me was concerned that this would rule me out of the upper echelons of conference interpreting, condemning me to be forever a generalist, whilst another part of me recognised that this was the nature of the market in the UK. I also now know that this ability to hop from one subject to another, to learn quickly and project the confidence of an expert where little-to-no expertise exists, is the interpreter’s special skill. And yet as it turns out, I find that, step by imperceptible step, my work has taken me in a certain direction…

Bethan Jones

Bethan is a freelance Japanese-English interpreter based in London, UK. She has been “full-time freelance” since 2010 and alongside interpreting and the odd bit of translation, dabbles in presenting for TV and live events. Her interpreting work spans the areas of business, culture, and beyond, and she has been fortunate enough to work with well-known figures such as Hirokazu Kore-eda, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, Makoto Shinkai, Sayaka Murata and Marie Kondo. https://bethanjonesinterpreter.com/

(Photo credit: Eddie Judd Photography)